Phlebitis

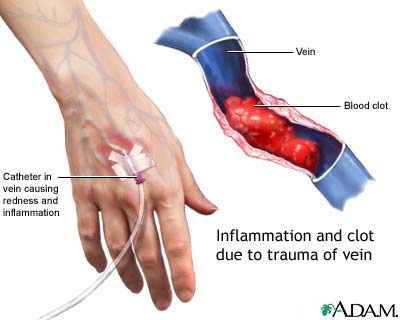

Phlebitis or Superficial thrombophlebitis may appear spontaneously in patients with varicose veins, in pregnant or postpartum women, or in patients with rare conditions such as thromboangiitis obliterans. It may also occur related to intravenous lines and in areas of trauma. It has been estimated to exceed 125,000 cases per year. The presence of superficial thrombophlebitis, especially if it occurs in a migratory pattern, suggests the presence of an abdominal cancer such as carcinoma of the pancreas (Trousseau’s sign).

In approximately 1% to 40% of cases, simultaneous DVT exists.Pulmonary Embolism is rare unless extension into the deep venous system occurs, although in the literature the incidence has been reported between 0% to 17%.

Patients usually present

- Complaining of localized extremity pain and redness.

- They will demonstrate areas of induration, erythema, and tenderness corresponding to dilated and thrombosed superficial veins.

- Over time, a firm cord usually develops.

- Unless the deep veins become involved, patients do not demonstrate generalized swelling.

- The presence of fever and shaking chills suggests septic/suppurative thrombophlebitis, usually from intravenous cannulation.

Superficial thrombophlebitis must be distinguished from a number of conditions including

- Ascending lymphangitis.

- Cellulitis.

- Erythema nodosum.

- Erythema induratum.

- Panniculitis.

Unlike these other disorders, superficial thrombophlebitis is well localized over a superficial vein.

Primary treatment of superficial thrombophlebitis is

- Administration of nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs, local heat, elevation, and support using either stockings or elastic wrap. Ambulation is encouraged. In most cases, symptoms will resolve or significantly improve within 7 to 10 days.

- Excision of the involved vein is recommended for recurrent phlebitis in the same vein segment, although the procedure is technically easier and the incisions tend to be smaller if the inflammation in the phlebitic vein is allowed to resolve its acute inflammation (usually waiting at least 6 months) before contemplating surgical excision. This obviously has to be modified if the indication for removal is septic/suppurative thrombophlebitis.

- If there is progressive proximal extension with involvement of the saphenofemoral junction (lower extremity) or cephalic-subclavian junction (upper extremity), ligation and resection of the vein at the junction should be performed. Alternatively, full-dose anticoagulation can be administered and the situation followed with monthly venous duplex scans.

- It is generally felt that medical management with anticoagulants versus surgical treatment is somewhat superior for minimizing complications and preventing subsequent DVT and PE development. On the other hand, surgical treatment with ligation at the saphenofemoral junction combined with stripping (with or without perforator interruption) appears to minimize superficial venous thrombus extension, which ultimately provides improved pain relief.

- Septic thrombophlebitis requires treatment with broad-spectrum intravenous antibiotics. If rapid resolution of the cellulitis occurs, no treatment beyond a short course of antibiotics and standard treatment for the superficial thrombophlebitis are required. However, if the patient becomes septic, excision of the infected vein is required. With positive blood cultures, an extended course of antibiotics specific for the identified organism is indicated additionally.

The majority of episodes of uncomplicated superficial thrombophlebitis respond to conservative management. However, the recurrence rate for superficial thrombophlebitis has been estimated between 15% to 20%.